As I mentioned in a former post, I just wrapped up a class on the history and politics of the Middle East, a class I have taught for a number of years now. One of its goals is for students to wrestle with the complexities of revolutionary movements in the Middle East, the most recent and particularly brutal incarnation being the so-called Islamic State. Not surprisingly, it is difficult for students to wrap their heads around this topic without falling back on reductionist explanations, which, as I mentioned two weeks ago, are problematic.

So what themes do we explore in order to place these movements in context and bring out the necessary tensions? There is more to be said than what is listed below, but for starters, here a few points to consider:

Historical precedent. We could debate whether or not Islam will inevitably be a political force in addition to just a religious one, but there is no question that, like Christianity in the pre-modern west, Islam has historically enveloped the political sphere. Indeed, it has represented a viable source of ideas and rhetoric for justifying political and revolutionary activism. Early examples would include the Kharijites, a movement that emerged in the 650s, although there is some debate how much IS and the Kharijites have in common. Examples since the 18th century would include the more familiar Wahhabi and recently more moderate Muslim Brotherhood movements, which have been active in the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt, respectively. And of course one of the best examples is the successful 1979 revolution carried out by Iran’s Shia Muslims.

Progressive-conservative integration. As agents of political change, revolutionary movements in Islam are by nature progressive – that is, their identity revolves around the augmentation or total destruction of the existing leadership. Yet sometimes revolution is employed as a means of reclaiming something from the past that has been cast off, but which is believed to be the key to addressing current problems. And this is the case for Islamic revolutionary movements. So this gives them a conservative (sometimes hyper-conservative) bent as well. Muslim revolutionaries often look to the past for inspiration – the eras before western imperialism, before the loss of cultural hegemony, before the inroads of socialism, secularism, and other symbols of modernity. And of course they look back to the era of Qur’anic inspiration, the Prophet, and the early Caliphate. While Muslims themselves debate the legitimacy of appropriating the past in this way, with this curious mixture of forward-looking and backward-looking impulses, revolutionaries hope to re-establish the past by working to change the present.

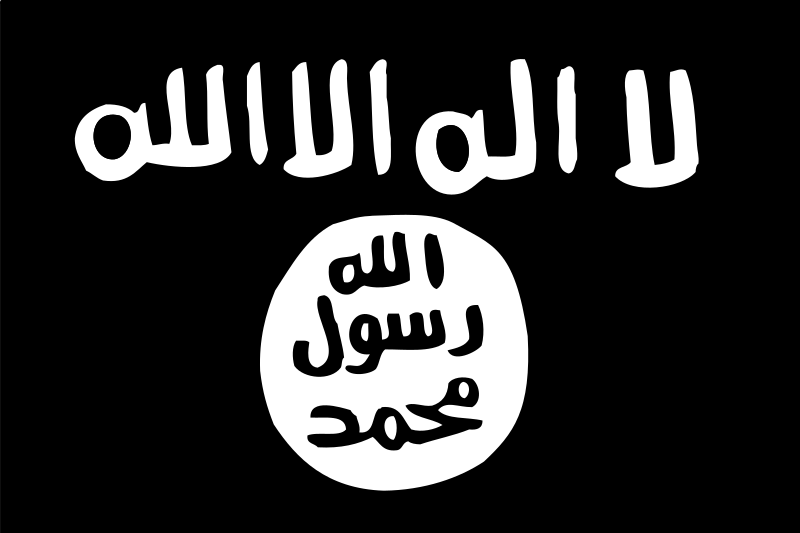

Flag of the Islamic State

Playing the “violence card.” Although Sufism would be a likely exception, Islam, like most other political and religious traditions, is not a pacifist faith. I like to tell students that the only Christians who can truly criticize Muslims for using violence for political gain are Quakers, Anabaptists, and others among the peace church tradition. Of course there is room for debate here and I usually get the desired banter. But the point remains. Unless we are pacifists, the violence card is always in our hand and it can be played whenever we believe it to be justified.

Now I realize this is a huge topic and there are all sorts of discussions we would have in a classroom that we cannot have in a blog post — the absolutely horrendous nature of IS’s tactics, as well as the nature of “just war” and redemptive violence (or the myth thereof), for example. Still, the reality is that Muslim revolutionaries will, like most of us, play the violence card when it is deemed “good” to do so. Although we can and should debate the morality of using violence, bloodless revolutions will always be the exception.

The significance of injustice. The greatest justification for playing the violence card is injustice. I was a fan of the television series The West Wing and remember the episode that aired in the wake of 9/11 when a bunch of high school kids asked Bradley Whitford’s character “Why are they trying to kill us?” I also remember George W. Bush’s answer to the same question. The real answer had more to do with resentment over the West’s long history of exploiting the Middle East than our American ideals. But the impact of the West’s presence in the Middle East is relevant to more than simply explaining anti-western sentiment in many sectors of the Middle East. It is also testament to the plight of the Muslim World after the fall of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I, which ushered in the most recent wave of western intervention in the Middle East.

The West is not to be blamed for the downward spiral of the Ottoman Empire, nor every injustice in the Middle East. It is true, however, that Islamic revolutions, like all others, gain momentum because people live in circumstances they believe to be unjust. Since the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the Middle East has been a patchwork quilt of failed and corrupt states, economic hardship, political experimentation, and sectarian fracturing. Revolutions are meant to rectify injustices. Rather than scratch our heads in disbelief when we see radical Muslims fomenting some revolution or another, we should instead look for the source of injustice. We will always find it. We may not believe that it legitimizes revolutionary behavior, but we will find it.

How do you spark Islamic Revolution? Invoke historical precedent, embrace a mixture of conservative and progressive impulses, find justification for playing the violence card, and rally around the deep feelings of injustice shared by many in the Muslim World.